On the Art of the Novel a Conversation With Milan Kunderaã¢ââ

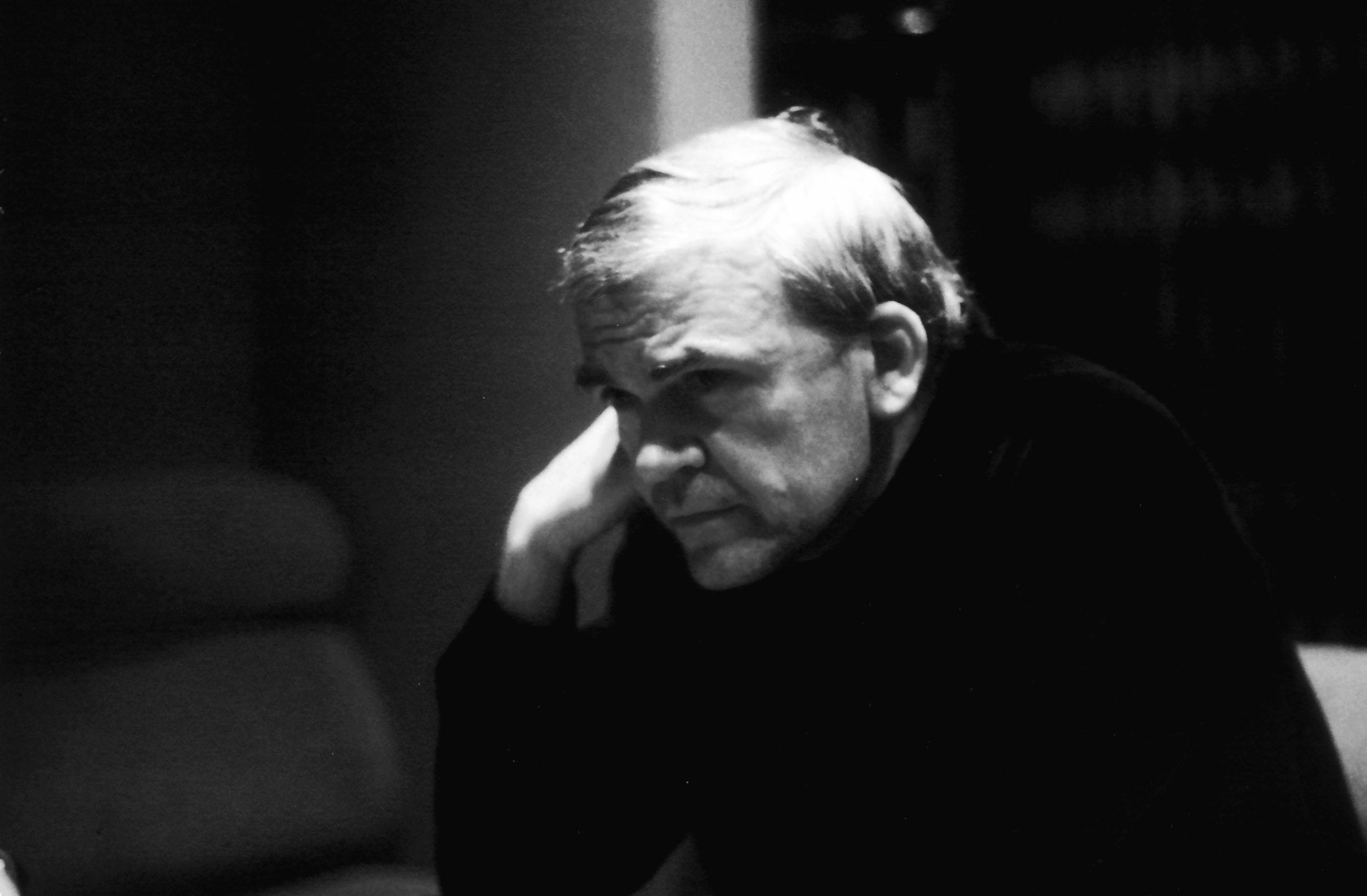

Milan Kundera, ca. 1980. Photograph by Elisa Cabot

Milan Kundera, ca. 1980. Photograph by Elisa Cabot

This interview is a production of several encounters with Milan Kundera in Paris in the fall of 1983. Our meetings took place in his attic apartment near Montparnasse. We worked in the small room that Kundera uses every bit his function. With its shelves total of books on philosophy and musicology, an old-fashioned typewriter and a table, it looks more similar a student's room than like the study of a globe-famous author. On one of the walls, two photographs hang next: one of his father, a pianist, the other of Leoš Janácek, a Czech composer whom he greatly admires.

We held several free and lengthy discussions in French; instead of a tape recorder, we used a typewriter, scissors, and gum. Gradually, amid discarded scraps of paper and after several revisions, this text emerged.

This interview was conducted before long after Kundera's most contempo book, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, had become an immediate best-seller. Sudden fame makes him uncomfortable; Kundera would surely hold with Malcolm Lowry that "success is like a horrible disaster, worse than a burn in one's abode. Fame consumes the habitation of the soul." Once, when I asked him nearly some of the comments on his novel that were appearing in the press, he replied, "I've had an overdose of myself!"

Kundera's wish not to talk about himself seems to be an instinctive reaction against the tendency of near critics to written report the author, and the author's personality, politics, and individual life, instead of the writer's works. "Disgust at having to talk about oneself is what distinguishes novelistic talent from lyric talent," Kundera told Le Nouvel Observateur.

Refusing to talk about oneself is therefore a style of placing literary works and forms squarely at the heart of attention, and of focusing on the novel itself. That is the purpose of this discussion on the art of composition.

INTERVIEWER

You lot take said that you feel closer to the Viennese novelists Robert Musil and Hermann Broch than to any other authors in modern literature. Broch thought—equally you do—that the age of the psychological novel had come to an end. He believed, instead, in what he chosen the "polyhistorical" novel.

MILAN KUNDERA

Musil and Broch saddled the novel with enormous responsibilities. They saw it equally the supreme intellectual synthesis, the terminal place where human being could still question the world equally a whole. They were convinced that the novel had tremendous synthetic ability, that it could be poesy, fantasy, philosophy, aphorism, and essay all rolled into one. In his letters, Broch makes some profound observations on this effect. Nevertheless, it seems to me that he obscures his own intentions by using the ill-chosen term "polyhistorical novel." It was in fact Broch's compatriot, Adalbert Stifter, a classic of Austrian prose, who created a truly polyhistorical novel in his Der Nachsommer [Indian Summer], published in 1857. The novel is famous: Nietzsche considered it to be one of the iv greatest works of German literature. Today, it is unreadable. It'due south packed with data about geology, botany, zoology, the crafts, painting, and architecture; but this gigantic, uplifting encyclopedia virtually leaves out homo himself, and his situation. Precisely because information technology is polyhistorical, Der Nachsommer totally lacks what makes the novel special. This is not the instance with Broch. On the contrary! He strove to discover "that which the novel alone tin discover." The specific object of what Broch liked to call "novelistic knowledge" is existence. In my view, the word "polyhistorical" must be defined as "that which brings together every device and every course of knowledge in order to shed low-cal on existence." Yep, I practice feel close to such an arroyo.

INTERVIEWER

A long essay you published in the mag Le Nouvel Observateur acquired the French to rediscover Broch. You speak highly of him, and withal you are also critical. At the end of the essay, you write: "All great works (just because they are great) are partly incomplete."

KUNDERA

Broch is an inspiration to us not only because of what he accomplished, but also considering of all that he aimed at and could not attain. The very incompleteness of his piece of work tin aid us sympathize the demand for new art forms, including: (ane) a radical stripping away of unessentials (in social club to capture the complexity of existence in the modern world without a loss of architectonic clarity); (two) "novelistic counterpoint" (to unite philosophy, narrative, and dream into a single music); (3) the specifically novelistic essay (in other words, instead of challenge to convey some apodictic message, remaining hypothetical, playful, or ironic).

INTERVIEWER

These three points seem to capture your entire artistic program.

KUNDERA

In order to make the novel into a polyhistorical illumination of existence, you need to primary the technique of ellipsis, the fine art of condensation. Otherwise, you fall into the trap of endless length. Musil's The Human Without Qualities is 1 of the two or iii novels that I love well-nigh. But don't ask me to adore its gigantic unfinished area! Imagine a castle so huge that the eye cannot take it all in at a glance. Imagine a cord quartet that lasts nine hours. There are anthropological limits—human proportions—that should not be breached, such as the limits of memory. When you have finished reading, you should all the same be able to retrieve the outset. If not, the novel loses its shape, its "architectonic clarity" becomes murky.

INTERVIEWER

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting is made up of vii parts. If you had dealt with them in a less elliptical fashion, you lot could have written seven unlike full-length novels.

KUNDERA

But if I had written seven independent novels, I would have lost the well-nigh of import thing: I wouldn't have been able to capture the "complexity of human existence in the modernistic world" in a unmarried volume. The fine art of ellipsis is absolutely essential. It requires that one always become directly to the centre of things. In this connection, I always recollect of a Czech composer I have passionately admired since childhood: Leoš JanáÄek. He is 1 of the greatest masters of mod music. His determination to strip music to its essentials was revolutionary. Of course, every musical limerick involves a great bargain of technique: exposition of the themes, their development, variations, polyphonic work (often very automated), filling in the orchestration, the transitions, et cetera. Today one can etch music with a computer, simply the computer ever existed in composers' heads—if they had to, composers could write sonatas without a single original idea, just by "cybernetically" expanding on the rules of composition. JanáÄek'south purpose was to destroy this figurer! Brutal juxtaposition instead of transitions; repetition instead of variation—and ever directly to the heart of things: only the note with something essential to say is entitled to exist. Information technology is nearly the same with the novel; it as well is encumbered by "technique," by rules that do the author's piece of work for him: present a character, describe a milieu, bring the activity into its historical setting, fill the lifetime of the characters with useless episodes. Every change of scene requires new expositions, descriptions, explanations. My purpose is like JanáÄek's: to rid the novel of the automatism of novelistic technique, of novelistic word-spinning.

INTERVIEWER

The second art course you mentioned was "novelistic counterpoint."

KUNDERA

The thought of the novel as a great intellectual synthesis almost automatically raises the trouble of "polyphony." This problem yet has to be resolved. Accept the 3rd part of Broch's novel The Sleepwalkers; it is made upwardly of five heterogeneous elements: (1) "novelistic" narrative based on the iii primary characters: Pasenow, Esch, Huguenau; (two) the personal story of Hanna Wendling; (three) factual description of life in a armed services infirmary; (4) a narrative (partly in verse) of a Conservancy Ground forces daughter; (5) a philosophical essay (written in scientific language) on the debasement of values. Each role is magnificent. Yet despite the fact that they are all dealt with simultaneously, in constant alternation (in other words, in a polyphonic manner), the five elements remain disunited—in other words, they do not found a true polyphony.

INTERVIEWER

By using the metaphor of polyphony and applying information technology to literature, exercise y'all non in fact make demands on the novel that it cannot mayhap live upward to?

KUNDERA

The novel tin can comprise outside elements in two means. In the course of his travels, Don Quixote meets various characters who tell him their tales. In this way, independent stories are inserted into the whole, fitted into the frame of the novel. This type of composition is often plant in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century novels. Broch, however, instead of fitting the story of Hanna Wendling into the master story of Esch and Huguenau, lets both unfold simultaneously. Sartre (in The Reprieve), and Dos Passos earlier him, likewise used this technique of simultaneity. Their aim, notwithstanding, was to bring together dissimilar novelistic stories, in other words, homogeneous rather than heterogeneous elements as in the case of Broch. Moreover, their employ of this technique strikes me as likewise mechanical and devoid of poetry. I cannot think of better terms than "polyphony" or "counterpoint" to describe this class of composition and, furthermore, the musical analogy is a useful one. For case, the first thing that bothers me about the third part of The Sleepwalkers is that the 5 elements are not all equal. Whereas the equality of all the voices in musical counterpoint is the basic ground rule, the sine qua non. In Broch's piece of work, the commencement element (the novelistic narrative of Esch and Huguenau) takes upward much more physical space than the other elements, and, fifty-fifty more important, it is privileged insofar equally it is linked to the 2 preceding parts of the novel and therefore assumes the task of unifying information technology. It therefore attracts more attention and threatens to turn the other elements into mere accompaniment. The second thing that bothers me is that though a fugue by Bach cannot do without any one of its voices, the story of Hanna Wendling or the essay on the reject of values could very well stand lonely as an contained work. Taken separately, they would lose nothing of their pregnant or of their quality.

In my view, the basic requirements of novelistic counterpoint are: (1) the equality of the various elements; (two) the indivisibility of the whole. I retrieve that the 24-hour interval I finished "The Angels," part three of The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, I was terribly proud of myself. I was sure that I had discovered the key to a new way of putting together a narrative. The text was made up of the post-obit elements: (1) an anecdote near ii female person students and their levitation; (2) an autobiographical narrative; (3) a critical essay on a feminist book; (4) a fable near an angel and the devil; (v) a dream-narrative of Paul Eluard flying over Prague. None of these elements could exist without the others, each one illuminates and explains the others equally they all explore a single theme and ask a single question: "What is an affections?"

Role six, also entitled "The Angels," is fabricated up of: (1) a dream-narrative of Tamina's death; (2) an autobiographical narrative of my begetter's decease; (iii) musicological reflections; (4) reflections on the epidemic of forgetting that is devastating Prague. What is the link betwixt my begetter and the torturing of Tamina by children? It is "the meeting of a sewing machine and an umbrella" on the table of one theme, to borrow Lautréamont's famous paradigm. Novelistic polyphony is poetry much more than technique. I can find no case of such polyphonic poetry elsewhere in literature, but I take been very astonished by Alain Resnais's latest films. His use of the art of counterpoint is beauteous.

INTERVIEWER

Counterpoint is less apparent in The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

KUNDERA

That was my aim. There, I wanted dream, narrative, and reflection to period together in an indivisible and totally natural stream. Only the polyphonic character of the novel is very hit in part half dozen: the story of Stalin's son, theological reflections, a political event in Asia, Franz's death in Bangkok, and Tomas's funeral in Bohemia are all linked by the aforementioned everlasting question: "What is kitsch?" This polyphonic passage is the pillar that supports the entire structure of the novel. Information technology is the key to the secret of its architecture.

INTERVIEWER

By calling for "a specifically novelistic essay," you expressed several reservations about the essay on the debasement of values which appeared in The Sleepwalkers.

KUNDERA

It is a terrific essay!

INTERVIEWER

Yous have doubts about the fashion information technology is incorporated into the novel. Broch relinquishes none of his scientific language, he expresses his views in a straightforward way without hiding behind one of his characters—the mode Mann or Musil would do. Isn't that Broch's real contribution, his new challenge?

KUNDERA

That is truthful, and he was well aware of his own courage. Simply at that place is also a risk: his essay can be read and understood equally the ideological central to the novel, as its "Truth," and that could transform the rest of the novel into a mere illustration of a thought. Then the novel'south equilibrium is upset; the truth of the essay becomes too heavy and the novel'south subtle architecture is in danger of collapsing. A novel that had no intention of expounding a philosophical thesis (Broch loathed that type of novel!) may air current up being read in exactly that style. How does one incorporate an essay into the novel? It is important to have one bones fact in mind: the very essence of reflection changes the minute information technology is included in the body of a novel. Exterior of the novel, one is in the realm of assertions: everyone'south philosopher, pol, concierge—is sure of what he says. The novel, all the same, is a territory where 1 does non make assertions; information technology is a territory of play and of hypotheses. Reflection inside the novel is hypothetical by its very essence.

INTERVIEWER

Only why would a novelist want to deprive himself of the right to express his philosophy overtly and assertively in his novel?

KUNDERA

Considering he has none! People oftentimes talk almost Chekhov's philosophy, or Kafka's, or Musil's. But just endeavor to detect a coherent philosophy in their writings! Fifty-fifty when they express their ideas in their notebooks, the ideas amount to intellectual exercises, playing with paradoxes, or improvisations rather than to assertions of a philosophy. And philosophers who write novels are goose egg only pseudonovelists who use the course of the novel in order to illustrate their ideas. Neither Voltaire nor Camus ever discovered "that which the novel lone can discover." I know of only one exception, and that is the Diderot of Jacques le fataliste. What a miracle! Having crossed over the boundary of the novel, the serious philosopher becomes a playful thinker. There is not one serious judgement in the novel—everything in it is play. That's why this novel is outrageously underrated in France. Indeed, Jacques le fataliste contains everything that French republic has lost and refuses to recover. In France, ideas are preferred to works. Jacques le fataliste cannot exist translated into the linguistic communication of ideas, and therefore it cannot be understood in the homeland of ideas.

INTERVIEWER

In The Joke, information technology is Jaroslav who develops a musicological theory. The hypothetical graphic symbol of his thinking is thus apparent. Just the musicological meditations in The Volume of Laughter and Forgetting are the author's, your ain. How am I then to understand whether they are hypothetical or assertive?

KUNDERA

It all depends on the tone. From the very first words, my intention is to give these reflections a playful, ironic, provocative, experimental, or questioning tone. All of office six of The Unbearable Lightness of Being ("The G March") is an essay on kitsch which expounds 1 main thesis: kitsch is the absolute deprival of the existence of shit. This meditation on kitsch is of vital importance to me. It is based on a groovy deal of idea, experience, study, and even passion. Yet the tone is never serious; information technology is provocative. This essay is unthinkable outside of the novel, information technology is a purely novelistic meditation.

INTERVIEWER

The polyphony of your novels also includes another element, dream-narrative. Information technology takes upwards the unabridged second role of Life Is Elsewhere, it is the footing of the sixth part of The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, and it runs through The Unbearable Lightness of Being past mode of Tereza's dreams.

KUNDERA

These passages are also the easiest ones to misunderstand, because people want to find some symbolic message in them. There is nothing to decipher in Tereza's dreams. They are poems nigh decease. Their meaning lies in their beauty, which hypnotizes Tereza. Past the mode, do y'all realize that people don't know how to read Kafka just because they desire to decipher him? Instead of letting themselves exist carried abroad by his unequaled imagination, they look for allegories and come up with zero but clichés: life is cool (or information technology is not absurd), God is across reach (or within reach), et cetera. You lot can empathize naught well-nigh fine art, particularly modern art, if y'all exercise not sympathize that imagination is a value in itself. Novalis knew that when he praised dreams. They "protect us against life'south monotony," he said, they "liberate us from seriousness by the please of their games." He was the first to understand the part that dreams and a dreamlike imagination could play in the novel. He planned to write the second volume of his Heinrich von Ofterdingen every bit a narrative in which dream and reality would be and so intertwined that i would no longer be able to tell them apart. Unfortunately, all that remains of that second volume are the notes in which Novalis described his artful intention. One hundred years later, his ambition was fulfilled by Kafka. Kafka's novels are a fusion of dream and reality; that is, they are neither dream nor reality. More than anything, Kafka brought almost an aesthetic revolution. An aesthetic phenomenon. Of class, no ane can repeat what he did. But I share with him, and with Novalis, the desire to bring dreams, and the imagination of dreams, into the novel. My way of doing so is by polyphonic confrontation rather than by a fusion of dream and reality. Dream-narrative is one of the elements of counterpoint.

INTERVIEWER

In that location is nothing polyphonic most the final part of The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, and yet that is probably the well-nigh interesting part of the book. Information technology is made up of fourteen chapters that recount erotic situations in the life of one man—Jan.

KUNDERA

Some other musical term: this narrative is a "theme with variations." The theme is the border beyond which things lose their meaning. Our life unfolds in the firsthand vicinity of that border, and we take chances crossing information technology at whatsoever moment. The fourteen chapters are fourteen variations of the aforementioned state of affairs'due south eroticism at the border between pregnant and meaninglessness.

INTERVIEWER

Yous accept described The Book of Laughter and Forgetting as a "novel in the course of variations." But is it still a novel?

KUNDERA

There is no unity of action, which is why it does not expect like a novel. People can't imagine a novel without that unity. Fifty-fifty the experiments of the nouveau roman were based on unity of activity (or of nonaction). Sterne and Diderot had amused themselves past making the unity extremely fragile. The journey of Jacques and his primary takes upward the bottom part of Jacques le fataliste; it'due south zilch more than than a comic pretext in which to fit anecdotes, stories, thoughts. Nevertheless, this pretext, this "frame," is necessary to make the novel feel similar a novel. In The Book of Laughter and Forgetting there is no longer any such pretext. It's the unity of the themes and their variations that gives coherence to the whole. Is it a novel? Aye. A novel is a meditation on beingness, seen through imaginary characters. The class is unlimited freedom. Throughout its history, the novel has never known how to take advantage of its countless possibilities. Information technology missed its chance.

INTERVIEWER

Only except for The Volume of Laughter and Forgetting, your novels are besides based on unity of action, although it is indeed of a much looser variety in The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

KUNDERA

Yeah, only other more important sorts of unity consummate them: the unity of the same metaphysical questions, of the aforementioned motifs and then variations (the motif of paternity in The Good day Political party, for instance). But I would like to stress above all that the novel is primarily built on a number of key words, like Schoenberg's series of notes. In The Volume of Laughter and Forgetting, the series is the following: forgetting, laughter, angels, "litost," the border. In the course of the novel these five fundamental words are analyzed, studied, defined, redefined, and thus transformed into categories of being. Information technology is built on these few categories in the aforementioned way as a business firm is built on its beams. The beams of The Unbearable Lightness of Being are: weight, lightness, the soul, the body, the Grand March, shit, kitsch, compassion, vertigo, strength, and weakness. Because of their categorical graphic symbol, these words cannot be replaced by synonyms. This always has to be explained over and over once again to translators, who—in their business concern for "expert style"—seek to avoid repetition.

INTERVIEWER

Regarding the architectural clarity, I was struck by the fact that all of your novels, except for one, are divided into seven parts.

KUNDERA

When I had finished my outset novel, The Joke, in that location was no reason to exist surprised that it had vii parts. Then I wrote Life Is Elsewhere. The novel was almost finished and information technology had vi parts. I didn't feel satisfied. All of a sudden I had the idea of including a story that takes place three years after the hero's death—in other words, outside the fourth dimension frame of the novel. This now became the sixth function of seven, entitled "The Eye-Aged Man." Immediately, the novel's architecture had get perfect. Later on, I realized that this sixth role was oddly coordinating to the sixth part of The Joke ("Kostka"), which likewise introduces an outside character, and likewise opens a secret window in the novel's wall. Laughable Loves started out as ten short stories. Putting together the terminal version, I eliminated 3 of them. The drove had get very coherent, foreshadowing the composition of The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. I character, Dr. Havel, ties the quaternary and 6th stories together. In The Volume of Laughter and Forgetting, the fourth and sixth parts are also linked past the same person: Tamina. When I wrote The Unbearable Lightness of Being, I was determined to break the spell of the number of seven. I had long since decided on a six-role outline. But the get-go role always struck me every bit shapeless. Finally, I understood that it was really made up of 2 parts. Like Siamese twins, they had to be separated by delicate surgery. The only reason I mention all this is to show that I am not indulging in some superstitious affectation well-nigh magic numbers, nor making a rational calculation. Rather, I am driven by a deep, unconscious, incomprehensible need, a formal archetype from which I cannot escape. All of my novels are variants of an architecture based on the number seven.

INTERVIEWER

The use of 7 neatly divided parts is certainly linked to your goal of synthesizing the nearly heterogeneous elements into a unified whole. Each office of your novel is always a world of its own, and is distinct from the others because of its special form. But if the novel is divided into numbered parts, why must the parts themselves also be divided into numbered chapters?

KUNDERA

The chapters themselves must likewise create a picayune globe of their ain; they must be relatively contained. That is why I go on pestering my publishers to brand sure that the numbers are clearly visible and that the capacity are well separated. The chapters are like the measures of a musical score! There are parts where the measures (chapters) are long, others where they are short, still others where they are of irregular length. Each part could take a musical tempo indication: moderato, presto, andante, et cetera. Role six of Life Is Elsewhere is andante: in a at-home, melancholy manner, it tells of the cursory encounter betwixt a middle-aged man and a young girl who has but been released from prison house. The last part is prestissimo; it is written in very short capacity, and jumps from the dying Jaromil to Rimbaud, Lermontov, and Pushkin. I first thought of The Unbearable Lightness of Being in a musical way. I knew that the terminal role had to be pianissimo and lento: it focuses on a rather short, uneventful period, in a single location, and the tone is serenity. I also knew that this part had to be preceded by a prestissimo: that is the function entitled "The Grand March."

INTERVIEWER

There is an exception to the rule of the number vii. In that location are only five parts to The Farewell Party.

KUNDERA

The Farewell Party is based on some other formal classic: it is absolutely homogeneous, deals with 1 subject, is told in i tempo; it is very theatrical, stylized, and derives its form from the farce. In Laughable Loves, the story entitled "The Symposium" is built exactly the aforementioned way—a farce in five acts.

INTERVIEWER

What do you hateful by farce?

KUNDERA

I hateful the emphasis on plot and on all its trappings of unexpected and incredible coincidences. Zilch has get as suspect, ridiculous, old-fashioned, trite, and tasteless in a novel as plot and its farcical exaggerations. From Flaubert on, novelists have tried to practice away with the artifices of plot. And so the novel has get duller than the dullest of lives. Withal there is another way to get around the suspect and worn-out attribute of the plot, and that is to free it from the requirement of likelihood. You tell an unlikely story that chooses to be unlikely! That'southward exactly how Kafka conceived Amerika. The way Karl meets his uncle in the commencement chapter is through a series of the most unlikely coincidences. Kafka entered into his first "sur-real" universe, into his first "fusion of dream and reality," with a parody of the plot—through the door of farce.

INTERVIEWER

But why did you choose the farce course for a novel that is not at all meant to be an entertainment?

KUNDERA

But it is an amusement! I don't sympathize the contempt that the French have for entertainment, why they are so ashamed of the word "divertissement." They run less gamble of being entertaining than of beingness tiresome. And they also run the risk of falling for kitsch, that sweetish, lying embellishment of things, the rose-colored light that bathes even such modernist works as Eluard'southward poetry or Ettore Scola's recent motion picture Le Bal, whose subtitle could be: "French history as kitsch." Yeah, kitsch, not entertainment, is the existent aesthetic disease! The neat European novel started out as entertainment, and every true novelist is cornball for it. In fact, the themes of those not bad entertainments are terribly serious—call up of Cervantes! In The Bye Party, the question is, does man deserve to live on this world? Shouldn't i "free the planet from man's clutches"? My lifetime ambition has been to unite the utmost seriousness of question with the utmost lightness of form. Nor is this purely an artistic ambition. The combination of a frivolous course and a serious field of study immediately unmasks the truth about our dramas (those that occur in our beds too as those that we play out on the nifty phase of History) and their awful insignificance. We experience the unbearable lightness of being.

INTERVIEWER

So you could just besides have used the championship of your latest novel for The Farewell Party?

KUNDERA

Every one of my novels could be entitled The Unbearable Lightness of Being or The Joke or Laughable Loves; the titles are interchangeable, they reverberate the modest number of themes that obsess me, define me, and, unfortunately, restrict me. Beyond these themes, I have nothing else to say or to write.

INTERVIEWER

There are, then, two formal archetypes of composition in your novels: (1) polyphony, which unites heterogeneous elements into an compages based on the number 7; (2) farce, which is homogeneous, theatrical, and skirts the unlikely. Could there exist a Kundera outside of these two archetypes?

KUNDERA

I always dream of some great unexpected infidelity. But I take not yet been able to escape my bigamous state.

Source: https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/2977/the-art-of-fiction-no-81-milan-kundera

Belum ada Komentar untuk "On the Art of the Novel a Conversation With Milan Kunderaã¢ââ"

Posting Komentar